Impact analysis of residential relocation on ownership, usage, and carbon-dioxide emissions of private cars

Impact analysis of residential relocation on ownership, usage, and carbon-dioxide emissions of private cars

住宅搬迁对私家车保有量、使用量和碳排放的影响分析

论文作者:薛飞;姚恩建

论文期刊:Energy

网址:Impact analysis of residential relocation on ownership, usage, and carbon-dioxide emissions of private cars-所有数据库 (webofscience.com)

关键词:住宅搬迁;出行行为;气候变化;温室气体排放;建筑环境;汽车保有量

1 摘要

很多学者都在探索住宅搬迁对出行行为的影响,但很少有研究讨论搬迁对出行二氧化碳排放的影响。本研究利用第五次北京居民出行调查和土地使用数据,建立了一个具有潜在变量的结构方程模型,探讨搬迁方向、建成环境变化、通勤距离和家庭社会经济属性对搬迁前后家庭汽车二氧化碳排放量变化的影响。结果表明,通勤距离、私人车辆购买量、家庭规模、电动自行车和公共交通智能卡的变化对碳排放量的变化有直接影响,而迁移方向、建筑环境潜在变量、家庭规模和家庭中青少年的数量则有间接影响。此外,本研究还提出了减少私家车出行碳排放以应对城市化的建议。这项研究可以帮助城市规划者和管理者了解住宅搬迁对车辆拥有、使用和相应的二氧化碳排放的影响,也可以为制定可持续城市和绿色交通的规划和管理政策提供参考。

2 研究背景

过去几十年来,人类活动产生的大量二氧化碳排放导致了全球变暖,并加速了极地地区冰川的融化。有报告表明,住宅搬迁会对出行行为产生影响,如出行方式选择和出行频率,尤其是汽车使用。同时,建筑环境对家庭出行相关碳排放也会影响。在城市化进程中,许多人可能会搬迁。人们改变住所不仅是因为建筑环境,还因为工作通勤距离、上学通勤距离、生活事件、居住区域、家庭社会经济属性和出行态度。

本研究使用2014年北京市家庭出行调查和相应的土地使用数据,分析2013年至2014年搬迁前后的汽车保有量和使用量及其二氧化碳排放量,以及汽车拥有和使用的社会经济属性,以及搬迁人口的碳排放。本研究侧重于在快速城市化过程中重新安置发展中国家的人口。不仅探讨了搬迁对汽车保有量和使用量的影响,还探讨了搬迁对于各类汽车出行(包括通勤出行)碳排放的影响。除此之外,本研究可以帮助政府和环境机构量化住宅搬迁对私人汽车相关出行碳排放的影响,并为他们在城市化趋势下制定绿色城市和低碳交通规划和管理政策提供参考。

3 数据

研究使用了第五次北京居民出行调查的数据。由于本研究主要探讨住宅搬迁对居民私家车出行相关碳排放的影响,考虑2013年和2014年搬迁的家庭拥有私家车,并选择通勤工人或学生作为本研究的对象。

同时,本研究旨在探讨住宅搬迁对居民私人车辆拥有和使用的影响。样本排除没有明确记录私人车辆购买时间和住宅搬迁时间的家庭以及数据记录不完整的家庭。最终,共选择了318个家庭的908名个人和347辆汽车进行研究。受调查家庭自愿选择搬迁,而不是因为公共工程或基础设施项目。

记录的数据包括这些家庭的社会经济属性、搬迁时间、当前和以前的居住地点、工作和学校地点、购买私人车辆的时间、车辆属性、搬迁前后私人车辆的平均月里程数以及平均月燃料成本。由于隐私保护,受访者之前的居住地点、当前居住地点、工作地点和学校地点均基于交通分析区统计数据。为了描述土地利用指标的变化,收集这些家庭住宅搬迁前后的建筑环境数据。这部分数据主要是2015年通过百度地图在线爬虫获得的。收集的数据包括不同和使用性质的兴趣点的类型和数量,以及移动前后住宅位置中心周围1公里缓冲半径内的道路交叉口数量。还测量了移动前后到最近地铁站和市中心(天安门广场)的距离。通过《北京统计年鉴》获得了搬迁前后住所所在地区的人口密度数据。计算了搬迁前后被调查家庭居住地的土地利用多样性,计算方式见公式(1)。土地利用多样性值范围从0(完全由一种土地利用类型主导)到1(所有土地利用类型的均衡分布)。

![]()

其中,L=r+o+c+p+l,r代表居住地周围1公里缓冲半径内的住宅用地的兴趣点数量,o代表居住地周围1公里缓冲半径内办公用地的关注点数量,c代表居住地周围1公里缓冲半径范围内的商业用地的利益点数量,p表示居住地周围1km缓冲半径内公共行政和服务用地的兴趣点数量,l表示居住地周围1公里缓冲半径内休闲用地的关注点数量。

IPCC采用“自上而下”的方法计算受调查家庭搬迁前后私家车出行的二氧化碳排放量。该方法是根据公式(2)通过对车辆燃油消耗统计数据计算得出:

![]()

![]()

其中,Ej是指第j个时间区间私家车的二氧化碳排放量,EFi是指i类燃料的二氧化碳排放系数,Vij是指家庭在第j个时间区间的i燃料消耗量,i是指燃料类型(其中1代表97#汽油,2代表93#汽油,3代表柴油),j是指第j个时间区间。

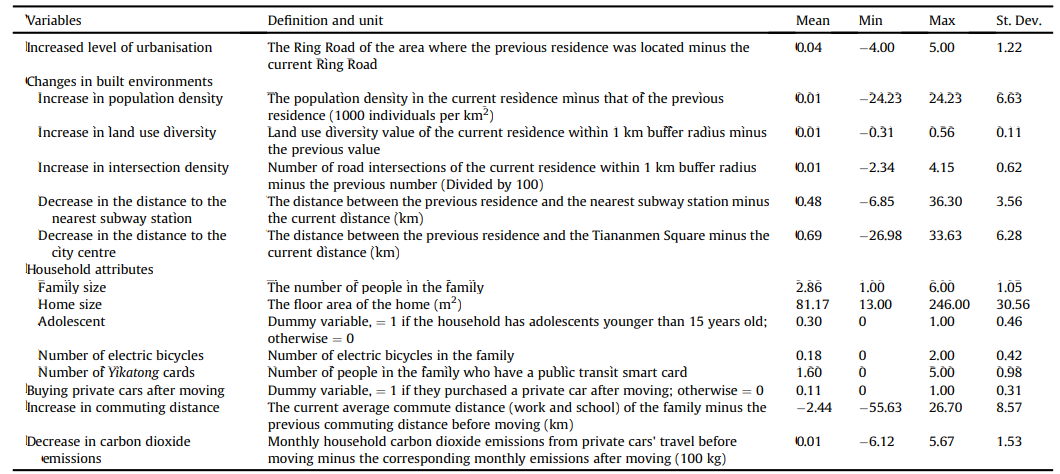

选定的变量及其定义如表1所示。在数据集中,受调查家庭的平均家庭规模为2.86人。研究发现,与以前的住所相比,更多的家庭搬到了更靠内的环路区域。北京是一个单中心城市,从中心到郊区有六条环城公路。四环以内的区域认为是市区,而外面是郊区。随着环城公路数量的增加,离市中心越来越远。北京市民经常通过环城路来确定他们的居住位置。与以前的住所相比,16.67%的家庭居住在人口更密集的住宅区。在新住宅周围1公里的缓冲半径内,46.54%的家庭拥有更高程度的土地利用多样性,43.40%的家庭拥有更多的道路交叉口。与此同时,43.71%的家庭新住宅距离最近的地铁站更远,40.25%的家庭新住所距离市中心更远。

表1变量基本统计参数

此外,29.87%的家庭有15岁以下的青少年。在中国,孩子一般在六岁上小学,十二岁上初中,十五岁上高中。国家规定为所有适龄学生提供免费的小学和初中教育,并允许12岁以上的人骑自行车。因此,在中国,父母通常在义务教育阶段接孩子放学,而在高中,学生通常自己上学。此外,16.67%的家庭拥有电动自行车,86.16%的家庭拥有一卡通,这是北京公共交通的智能交通卡,包括成人卡和学生卡。使用成人卡乘车可享受50%的折扣,学生卡可享受75%的折扣。11.01%的家庭在搬迁后购买了汽车。51.89%的家庭在搬迁后平均通勤距离(上班和上学)更短。44.65%的家庭乘坐私家车出行的月平均二氧化碳排放量低于以前。

4 方法和结果

4.1 结构方程建模方法

本研究建立了一个结构方程模型(SEM),该模型考虑了私家车车主的家庭社会经济属性、住宅所在地的建筑环境和通勤距离,以探讨住宅所在地变化对私家车拥有和使用及其二氧化碳排放的影响。

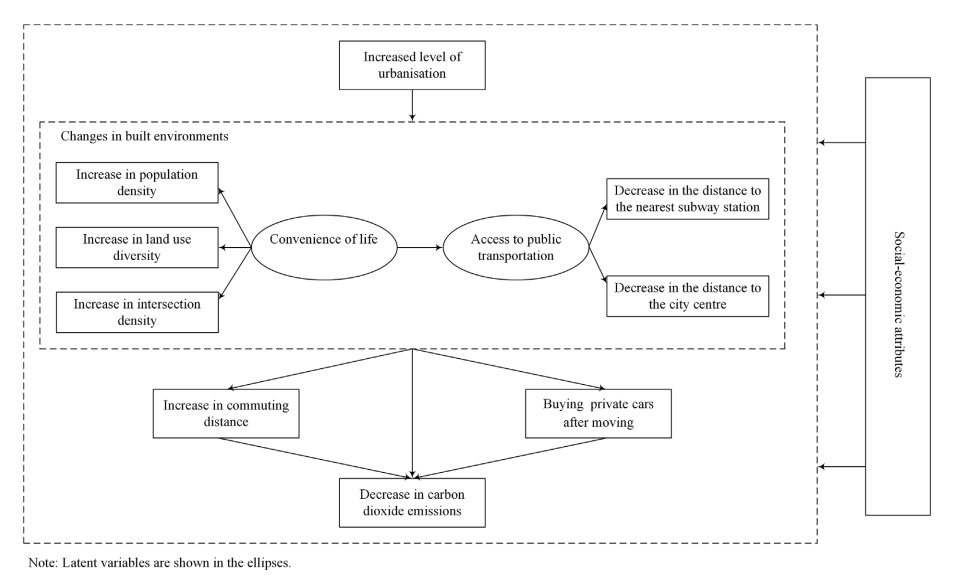

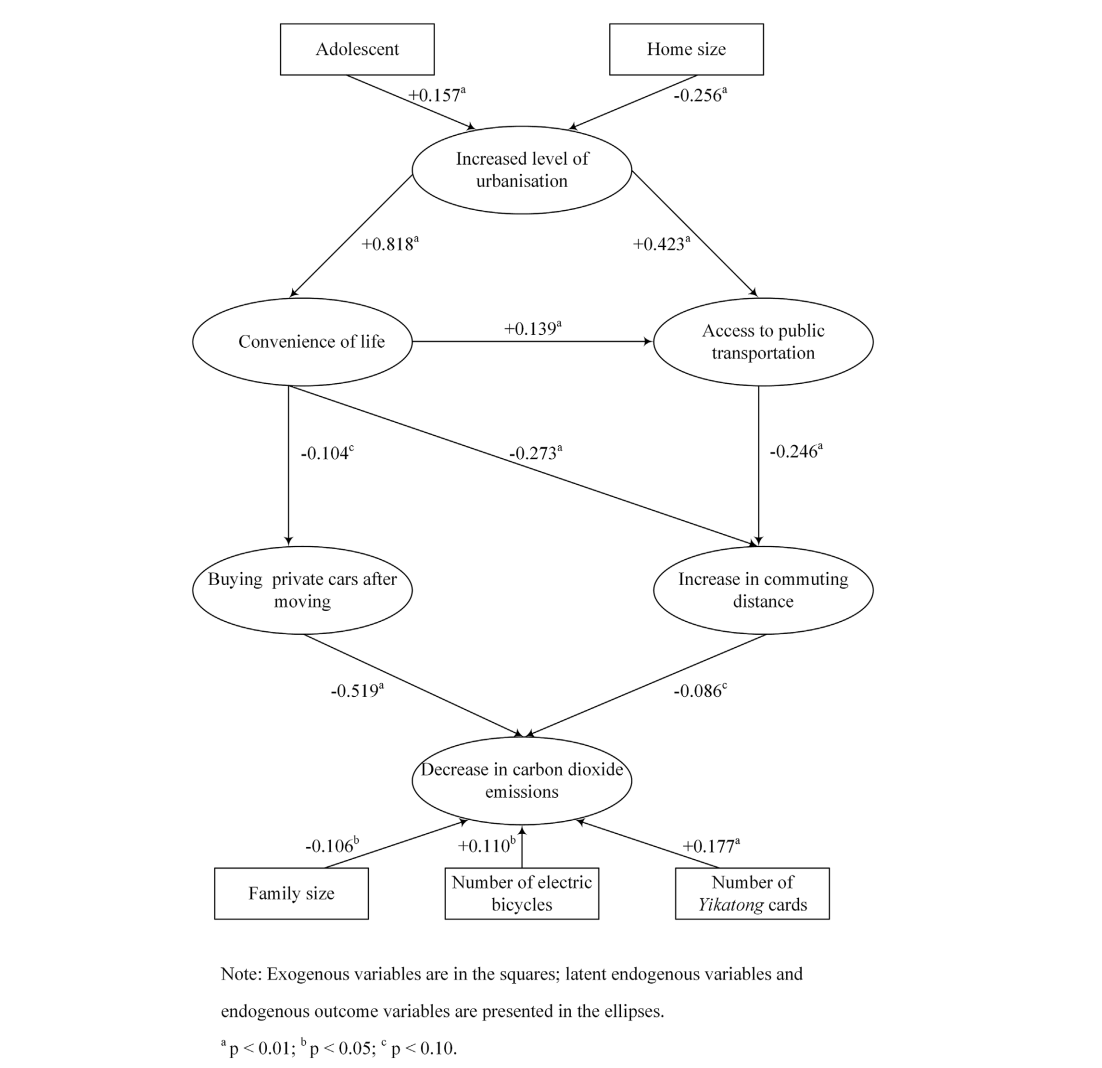

建立的SEM如图1所示。构建了两个潜在变量,以表示搬迁后建筑环境的相应变化,即生活便利性和公共交通便利性。具体来说,生活的便利性是通过人口密度、土地利用多样性和交叉口密度的增加来衡量的。公共交通的便利性是通过距离最近的地铁站和市中心的距离的减少来衡量的。然后,城市化水平的提高、通勤距离的增加、移动后购买私家车以及二氧化碳排放的减少选为内生变量。家庭社会经济属性设定为外生变量。建筑环境和通勤距离的变化,以及搬迁后购买私家车和家庭社会经济属性的变化对排放变化有直接影响。住宅搬迁方向具有间接影响。

图1概念模型框架

在Mplus软件中采用极大似然法估计假设模型。在估计过程中,去除了不重要的路径(p>0.1),重新校准,最后获得了校准结果。选择广泛采用的测试指标来测试估计模型的拟合优度。选定的指数包括chi-squares与自由度的比率(c2=df)、比较拟合指数(CFI)、Tucker Lewis指数(TLI)、近似均方根误差(RMSEA)和标准化均方根回归(SRMR)。

4.2 结果

4.2.1 拟合度

所构建的SEM呈现的卡方值为110.61,具有63个自由度,因此c2=df为1.756。同时,CFI等于0.964,TLI等于0.954,RMSEA等于0.049,SRMR等于0.041。与良好拟合模型的每个评估指标的参考值相比,具体而言,c2=df<3,CFI>0.90,TLI>0.900,RMSEA<0.05,SRMR<0.05,可以发现,所提出的模型很好地拟合了数据。

4.2.2 测量模型结果

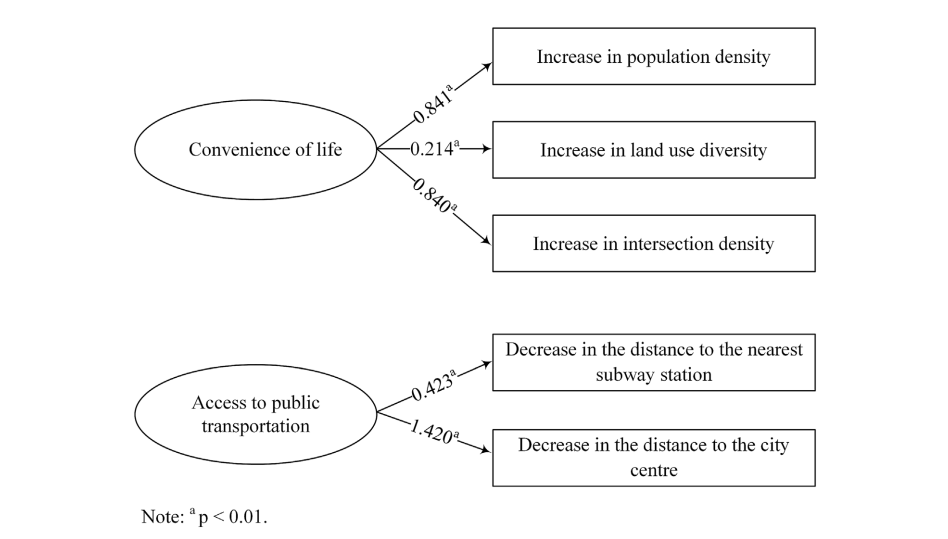

图2描述了两个潜在测量模型的估计结果,这两个模型描述了移动前后住宅区建成环境的变化。从测量模型结果可以看出,两个建成环境指标的潜在结构都很重要。具体而言,生活便利性的标准化系数分别为0.841、0.214和0.840。公共交通的标准化系数分别为0.423和1.420。

图2.潜在测量模型结果

生活便利性潜在结构的正系数表明搬迁后,与故居相比,新居具有更高的人口密度、土地利用多样性和交叉密度,这表明新居拥有更便利的生活服务设施。同时,公共交通可达性潜在结构的正系数表明,因为市中心的公共交通设施密度高于郊区,新住宅比旧住宅更靠近最近的地铁站和市中心。第二个建筑环境指标的高值表明当前住宅比前一个住宅更方便,更接近公共交通服务。

4.2.3 结构模型结果

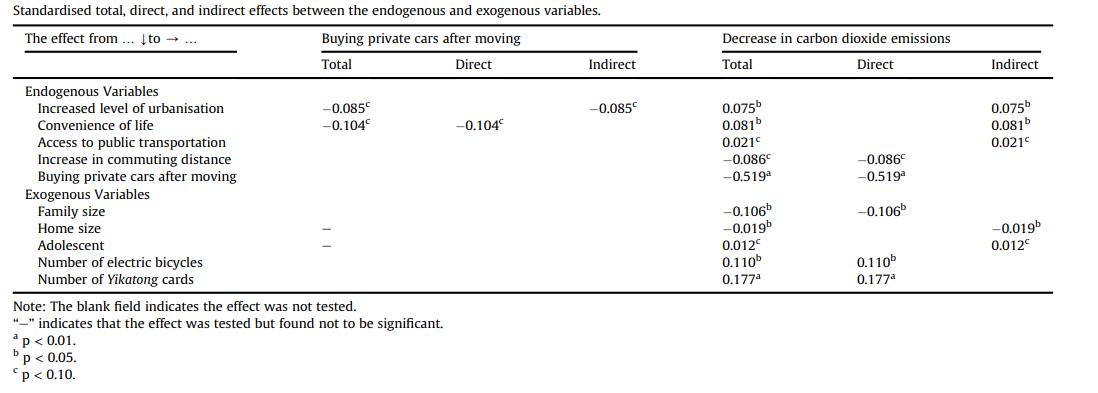

根据图3所示的测试结构模型和标准化总量,表2显示了内生变量和外生变量之间的直接和间接影响。

研究首先分析了直接影响。经测试的结构模型表明,城市化水平的提高对生活的便利性和公共交通的便利性有显著的积极影响。当居民搬到更多的城市地区时,生活服务和公共交通设施的便利性将得到改善。生活的便利性对公共交通的使用产生了显著的积极影响。结果表明,生活服务设施的便利性与公共交通设施的使用呈正相关,即当人们选择搬迁地点时,他们可能会选择比以前的住所更便利的生活服务和公共交通设施。同样,生活的便利性和公共交通的便利性对通勤距离的增加都有显著的负面影响。研究表明,搬迁到生活服务设施和公共交通设施较少的地方的居民可能会经历更长的通勤距离。结果也表明建筑环境会影响人们的通勤生活的便利性对搬家后购买私家车有显著的负面影响。这表明,周围环境会影响人们购买私人车辆,特别是与生活便利性有关。研究发现,通勤距离的增加和搬迁后私家车的购买都对二氧化碳排放产生了显著的负面影响。搬到一个让家庭成员通勤时间更长的地方会产生更多的汽车出行,从而导致更多的二氧化碳排放。搬迁后购买私家车也会增加二氧化碳排放量。

图3.测试结构模型的路径图

表2内生变量和外生变量之间的标准化总、直接和间接影响

就家庭社会经济属性而言,家庭中的青少年在城市化水平的提高方面经历了显著的积极影响,而家庭规模对其产生了显著的负面影响,因为城市地区的学校密度和重点学校数量普遍较高。父母可能会搬到城市地区,以减少孩子上学的通勤时间或为他们提供更好的学校。由于城市地区的高房价,家庭规模或希望居住在更大空间的家庭可以选择在郊区租或买更大的住宅,以更低的成本享受足够的居住空间。此外,研究发现,家庭中电动自行车的数量和一卡通的数量对二氧化碳排放的减少都有显著的积极影响。结果证明,电动自行车和公共交通智能卡的使用可以减少机动出行造成的碳排放。家庭规模对二氧化碳排放产生负面影响。对于家庭规模较大的家庭搬迁到郊区,他们也可能会增加私家车的使用,增加排放量。

本研究同时探讨了间接影响。研究发现,城市化水平的提高对搬家后购买私家车有显著的间接负面影响。人们迁移到城市化水平高的地区将减少对私家车的需求。此外,城市化水平的提高、生活的便利性、公共交通的便利性以及家庭中青少年的数量对减少搬迁后的二氧化碳排放有间接的积极影响,而家庭规模有间接的负面影响。对于家庭规模较大的家庭搬迁到房价较低、居住空间较大的郊区,由于郊区公共交通不便,将更多地使用私人车辆以方便出行,排放量也将增加。相比之下,对于搬到城市化水平较高的地区的家庭来说,那里有更为便利的生活设施和公共交通,他们可以减少使用私家车,从而减少相应的碳排放。对于那些为了减少孩子上学的通勤时间或为他们提供更好的上学机会而搬到城市地区的父母来说,他们也可以减少私家车的使用,从而减少排放。

5 结论

本研究通过构建一个包含两个潜在变量的结构方程模型,研究家庭社会经济属性、搬迁方向、住宅建成环境变化、通勤距离、家庭车辆拥有量和使用量以及搬迁前后碳排放之间的相关性。生活的便利性对搬家后购买私家车有直接的负面影响,而城市化水平的提高则有间接的负面影响。对于碳排放的变化,通勤距离的增加、重新安置后购买私家车的数量以及家庭规模都会对二氧化碳排放产生直接的负面影响,而电动自行车的数量和家庭中的一卡通公交卡的数量也会产生直接的正面影响。此外,城市化水平的提高、生活的便利性、公共交通的便利性以及家庭中青少年的数量对二氧化碳排放有直接的积极影响,而家庭规模则产生间接的负面影响。

6 参考文献

[1] European Environment Agency. Greenhouse gas emissions from transport.2018.

[2] Gately CK, Hutyra LR, Wing IS. Cities, traffic, and CO2: a multidecadal assessment of trends, drivers, and scaling relationships. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015;112:4999e5004. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1421723112.

[3] Wu X, Tao T, Cao J, Fan Y, Ramaswami A. Examining threshold effects of built environment elements on travel-related carbon-dioxide emissions. Transport Res Transport Environ 2019;75:1e12. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.trd.2019.08.018.

[4] Cao X, Yang W. Examining the effects of the built environment and residential self-selection on commuting trips and the related CO2 emissions: an empirical study in Guangzhou, China. Transport Res Transport Environ 2017;52: 480e94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2017.02.003.

[5] Dennehy ER, O Gallach oir BP. Ex-post decomposition analysis of passenger car energy demand and associated CO2 emissions. Transport Res Transport Environ 2018;59:400e16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2018.01.012.

[6] Hofer C, Jager G, Füllsack M. Large scale simulation of CO2 emissions caused € by urban car traffic: an agent-based network approach. J Clean Prod 2018;183: 1e10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.113.

[7] Li Y, Du Q, Lu X, Wu J, Han X. Relationship between the development and CO2 emissions of transport sector in China. Transport Res Transport Environ 2019;74:1e14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2019.07.011.

[8] Yuan RQ, Tao X, Yang XL. CO 2 emission of urban passenger transportation in China from 2000 to 2014. Adv Clim Change Res 2019;10:59e67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accre.2019.03.005.

[9] Day J, Cervero R. Effects of residential relocation on household and commuting expenditures in Shanghai, China. Int J Urban Reg Res 2010;34:762e88. https:// doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2010.00916.x.

[10] Zhao P. Sustainable urban expansion and transportation in a growing megacity: consequences of urban sprawl for mobility on the urban fringe of Beijing. Habitat Int 2010;34:236e43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2009.09.008.

[11] Zhao P, Zhang Y. Travel behaviour and life course: examining changes in car use after residential relocation in Beijing. J Transport Geogr 2018;73:41e53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2018.10.003.

[12] Guan X, Wang D. Residential self-selection in the built environment-travel behavior connection: whose self-selection? Transport Res Transport Environ 2019;67:16e32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2018.10.015.

[13] Lin T, Wang D, Zhou M. Residential relocation and changes in travel behavior: what is the role of social context change? Transport Res Pol Pract 2018;111: 360e74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2018.03.015.

[14] United Nations Human Settlements Programme. UN-Habitat. 2020.

[15] Beenackers MA, Foster S, Kamphuis CBM, Titze S, Divitini M, Knuiman M, Van Lenthe FJ, Giles-Corti B. Taking up cycling after residential relocation: built environment factors. Am J Prev Med 2012;42:610e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.amepre.2012.02.021.

[16] De Vos J, Derudder B, Van Acker V, Witlox F. Reducing car use: changing attitudes or relocating? The influence of residential dissonance on travel behavior. J Transport Geogr 2012;22:1e9. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.jtrangeo.2011.11.005.

[17] De Vos J, Ettema D, Witlox F. Changing travel behaviour and attitudes following a residential relocation. J Transport Geogr 2018;73:131e47. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2018.10.013.

[18] De Vos J, Ettema D, Witlox F. Effects of changing travel patterns on travel satisfaction: a focus on recently relocated residents. Travel Behav Soc 2019;16:42e9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2019.04.001.

[19] Yang M, Wu J, Rasouli S, Cirillo C, Li D. Exploring the impact of residential relocation on modal shift in commute trips: evidence from a quasilongitudinal analysis. Transport Pol 2017;59:142e52. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tranpol.2017.07.005.

[20] Zarabi Z, Manaugh K, Lord S. The impacts of residential relocation on commute habits: a qualitative perspective on households' mobility behaviors and strategies. Travel Behav Soc 2019;16:131e42. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.tbs.2019.05.003.

[21] Choi K, Zhang M. The net effects of the built environment on household vehicle emissions: a case study of Austin, TX. Transport Res Transport Environ 2017;50:254e68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2016.10.036.

[22] Modarres A. Commuting and energy consumption: toward an equitable transportation policy. J Transport Geogr 2013;33:240e9. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2013.09.005.

[23] Wang X, Khattak A, Zhang Y. Is smart growth associated with reductions in carbon dioxide emissions? Transport Res Rec 2013:62e70. https://doi.org/ 10.3141/2375-08.

[24] Wang Y, Yang L, Han S, Li C, Ramachandra TV. Urban CO2 emissions in Xi’an and Bangalore by commuters: implications for controlling urban transportation carbon dioxide emissions in developing countries. Mitig Adapt Strategies Glob Change 2017;22:993e1019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027- 016-9704-1.

[25] Xu L, Cui S, Tang J, Yan X, Huang W, Lv H. Investigating the comparative roles of multi-source factors influencing urban residents' transportation greenhouse gas emissions. Sci Total Environ 2018;644:1336e45. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.07.072.

[26] Adhikari B, Hong A, Frank LD. Residential relocation, preferences, life events, and travel behavior: a pre-post study. Res Transport Business Manag 2020;36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rtbm.2020.100483.

[27] De Vos J, Witlox F. Do people live in urban neighbourhoods because they do not like to travel? Analysing an alternative residential self-selection hypothesis. Travel Behav Soc 2016;4:29e39. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.tbs.2015.12.002.

[28] Ettema D, Nieuwenhuis R. Residential self-selection and travel behaviour:

what are the effects of attitudes, reasons for location choice and the built enviroment? J Transport Geogr 2017;59:146e55. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.jtrangeo.2017.01.009.

[29] Fatmi MR, Chowdhury S, Habib MA. Life history-oriented residential location

choice model: a stress-based two-tier panel modeling approach. Transport Res Pol Pract 2017;104:293e307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2017.06.006.

[30] Guidon S, Wicki M, Bernauer T, Axhausen K. The social aspect of residential location choice: on the trade-off between proximity to social contacts and commuting. J Transport Geogr 2019;74:333e40. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.jtrangeo.2018.12.008.

[31] Kroesen M. Residential self-selection and the reverse causation hypothesis: assessing the endogeneity of stated reasons for residential choice. Travel Behav Soc 2019;16:108e17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2019.05.002.

[32] Schwanen T, Mokhtarian PL. The extent and determinants of dissonance between actual and preferred residential neighborhood type. Environ Plann Plann Des 2004;31:759e84. https://doi.org/10.1068/b3039.

[33] Wolday F, Næss P, Cao (Jason) X. Travel-based residential self-selection: a qualitatively improved understanding from Norway. Cities 2019;87:87e102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2018.12.029.

[34] Xue F, Yao E, Jin F. Exploring residential relocation behavior for families with workers and students; a study from Beijing, China. J Transport Geogr 2020;89: 102893. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102893.

[35] Yu B, Zhang J, Li X. Dynamic life course analysis on residential location choice. Transport Res Pol Pract 2017;104:281e92. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.tra.2017.01.009.

[36] De Vos J, Cheng L, Witlox F. Do changes in the residential location lead to changes in travel attitudes? A structural equation modeling approach. Transportation 2021;48:2011e34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-020- 10119-7.

[37] Hong J, Goodchild A. Land use policies and transport emissions: modeling the impact of trip speed, vehicle characteristics and residential location. Transport Res Transport Environ 2014;26:47e51. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.trd.2013.10.011.

[38] Zahabi SAH, Miranda-Moreno L, Patterson Z, Barla P, Harding C. Transportation greenhouse gas emissions and its relationship with urban form, transit accessibility and emerging green technologies: a montreal case study. Procedia - Soc Behav Sci 2012;54:966e78. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.sbspro.2012.09.812.

[39] Ao Y, Yang D, Chen C, Wang Y. Effects of rural built environment on travelrelated CO2 emissions considering travel attitudes. Transport Res Transport Environ 2019;73:187e204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2019.07.004.

[40] Zhang Y, Yao E, Zhang R, Xu H. Analysis of elderly people's travel behaviours during the morning peak hours in the context of the free bus programme in Beijing, China. J Transport Geogr 2019;76:191e9. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.jtrangeo.2019.04.002.

[41] Beijing Statistical Yearbook. Beijing municipal bureau of statistics. 2013. [42] Beijing Statistical Yearbook. Beijing municipal bureau of statistics. 2014.

[43] Bhat CR, Guo JY. A comprehensive analysis of built environment characteristics on household residential choice and auto ownership levels. Transp Res Part B Methodol 2007;41:506e26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trb.2005.12.005.

[44] Van Acker V, Witlox F. Car ownership as a mediating variable in car travel behaviour research using a structural equation modelling approach to identify its dual relationship. J Transport Geogr 2010;18:65e74. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2009.05.006.

[45] IPCC. IPCC guidelines for national greenhouse gas inventories. 2006 [Geneva]. [46] Xue F, Yao E. Adopting a random forest approach to model household residential relocation behavior. Cities 2022;125. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.cities.2022.103625.

[47] Ding C. Urban spatial development in the land policy reform era: evidence from Beijing. Urban Stud 2004;41:1889e907. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 0042098042000256305.

[48] Wang D, Lin T. Built environment, travel behavior, and residential selfselection: a study based on panel data from Beijing, China. Transportation 2019;46:51e74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-017-9783-1.

[49] Golob TF. Structural equation modeling for travel behavior research. Transp Res Part B Methodol 2003;37:1e25. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-2615(01) 00046-7.

[50] Aditjandra PT, Cao X, Mulley C. Understanding neighbourhood design impact on travel behaviour: an application of structural equations model to a British metropolitan data. Transport Res Pol Pract 2012;46:22e32. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tra.2011.09.001.

[51] Cheng L, Chen X, Yang S, Wu J, Yang M. Structural equation models to analyze activity participation, trip generation, and mode choice of low-income commuters. Transport Lett 2019;11:341e9. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 19427867.2017.1364460.

[52] Liu S, Yao E, Yamamoto T. Does urban rail transit discourage people from owning and using cars? Evidence from Beijing, China. J Adv Transport 2018;2018. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/1835241.

[53] Soltani M, Rahmani O, Ghasimi DSM, Ghaderpour Y, Pour AB, Misnan SH, Ngah I. Impact of household demographic characteristics on energy conservation and carbon dioxide emission: case from Mahabad city, Iran. Energy 2020;194:116916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2020.116916.

[54] Yung Y. Introduction to structural equation modeling using the CALIS procedure in SAS/STAT software. Cary, NC: the SAS Press; 2010.

[55] Ji S, Cherry CR, Bechle MJ, Wu Y, Marshall JD. Electric vehicles in China: emissions and health impacts. Environ Sci Technol 2012;46:2018e24. https:// doi.org/10.1021/es202347q.

[56] Jones T, Harms L, Heinen E. Motives, perceptions and experiences of electric bicycle owners and implications for health, wellbeing and mobility. J Transport Geogr 2016;53:41e9. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.jtrangeo.2016.04.006.

[57] Popovich N, Gordon E, Shao Z, Xing Y, Wang Y, Handy S. Experiences of electric bicycle users in the sacramento, California area. Travel Behav Soc 2014;1:37e44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2013.10.006.

[58] Huang M-T, Zhai P-M. Achieving Paris Agreement temperature goals requires carbon neutrality by middle century with far-reaching transitions in the whole society. Adv Clim Change Res 2021;21:281e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.accre.2021.03.004.