An analysis of commute mode choice behavior considering the impacts of built environment in Beijing

论文题目:An analysis of commute mode choice behavior considering the impacts of built environment in Beijing(考虑建成环境影响的北京市通勤方式选择行为分析)

论文作者:王朝晖,杨扬,姚恩建,朱宇婷,饶宗皓

期刊名称:Transportation Letters

网址:https://doi.org/10.1080/19427867.2021.1938908

关键词:方式选择,建成环境,通勤者,混合嵌套logit模型,弹性分析

1 摘要

交通拥堵和环境污染的担忧促使人们对建成环境对通勤者方式选择行为的影响进行了更多的研究。本文旨在利用北京市第五次家庭出行调查对通勤者的出行方式选择行为进行综合分析。采用混合嵌套logit模型,探讨了方式属性和建成环境变量对通勤者方式选择的影响。结果表明,所提出的混合嵌套logit模型优于标准多项logit模型和嵌套logit模型。估算结果表明,非机动车出行方式的通勤者更关注起终点距离。土地利用结构和密度对减少汽车偏好有显著影响,仅在工作区域有显著影响。此外,本研究将公交车和地铁等公共交通方式视为一组,其中任何一种交通方式的便捷性变化都会影响通勤者对整个公共交通系统的偏好。

2 研究背景

随着汽车保有量和使用量的增加,北京的交通拥堵和环境污染问题日益严重,尤其是在通勤时间上。为了解决这些问题并管理日益增长的汽车交通需求,北京政府提出并实施了多种限行政策,包括摇号限行政策、私家车尾号限行政策等。然而,这些限制政策只是治标不治本,未来可能会复发,因为出行者的驾驶偏好并没有改变,仍然处于较高的水平。因此,如何制定解决方案,使乘客的出行行为从私家车转向公共交通越来越受到交通部门的关注。

混用建成环境和改善公共交通系统被广泛认为是减少旅行者驾驶偏好的两种解决方案。进而从根本上解决汽车能耗、排放、拥堵的增长问题。但由于上述两种解决方案需要大量的支持(包括政策、资金、居民等),通常很难在老牌大城市中使用。为了解决拥堵、污染等问题,北京政府从2014年开始对城市进行重新规划和重建。北京市行政中心占地面积约812平方公里,包括数十个行政部门,已经完成规划,将于2035年基本建成。为了保证重建的有效性,有必要首先了解出行者,特别是通勤者的方式选择行为。

本文旨在对北京市通勤者的出行方式选择行为进行综合分析。本文的贡献总结如下。

本文考虑了数据库的时效性和综合性。本文的分析基于北京市交通委员会最近的一次出行调查,即第五次家庭出行调查。每个家庭都完成了一份出行调查,记录了所有家庭成员在指定一天的活动,包括活动参与的目的、起源地和目的地、出行方式、出行时间、出发时间等。本次调查在2014年9月1日至11月1日期间调查了北京16个区0.52%的人口(约101,815人,来自40,003户家庭),并全部被记录下。由于出行调查是在每个区随机进行的,因此可以认为出行调查的样本代表了整个北京市人口。此外,为了提高调查的有效性,采用了一系列的政策和质量控制方法。因此,统计偏差被控制在一定的范围内。

本文建立了混合嵌套logit (Nested Logit, NL)模型来捕捉北京市居民的方式选择行为。讨论了各变量对方式选择的影响。然后,根据模型估计的参数,计算出行时间的观测值。最后,采用直接弹性和交叉弹性来深入了解建成环境如何影响通勤者的方式选择。这些结果对于北京市的公共政策和规划应用具有一定的参考价值。

3 模型解释

3.1 模型结构

对于方式选择模型,模型的结构通常是基于估计的方式类型和它们之间的未观察属性。本文考虑了汽车、公共汽车、地铁、自行车和步行五种出行方式。正如以往大多数研究所考虑的那样,在使用基于非机动车的随机误差项中,假设自行车和步行具有共同的分担量。在公共机动车的基础上,采用随机误差条件假定公交和地铁有共同的分担量。由于并非所有的模态在随机误差项中都假定有共同分担量,因此NL公式比MNL (Multinomial Nested Logit)更合适。

3.2 方式选择模型

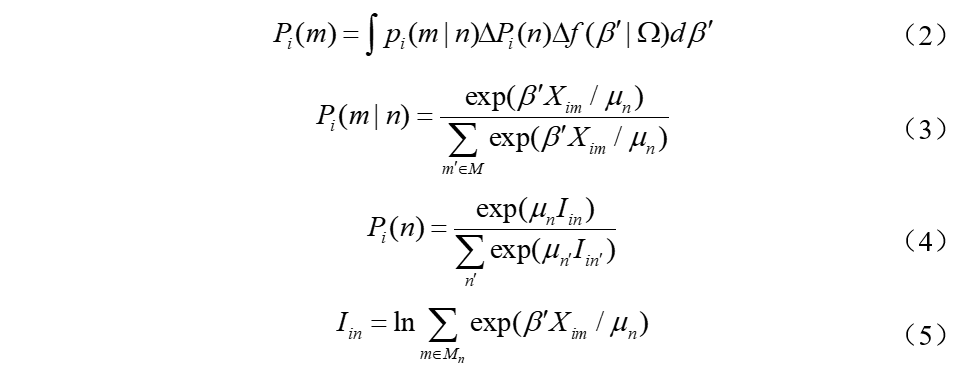

在混合NL模型中,个体i与备选方式m相关联的随机效用可以写成:

![]()

式中,是效用参数向量,是自变量向量,是效用函数的误差分量。

在给定的混合NL模型中,个体i选择方式m的概率可以表示为:

式中, 是个体i在n种方式中选择方式m的概率,是个体i在n中的概率,代表概率密度函数,表示描述概率密度函数(均值和方差)的参数向量,M表示方式选择集合,是嵌套n中的方式选择集合,表示嵌套的不相似参数,与标准NL模型相似,取值范围在。是嵌套n对单个i的对数和函数。

3.3 数据源

用于建模过程的样本数据是从家庭出行行为调查数据中提取的,包括从家到工作场所的所有通勤行程。

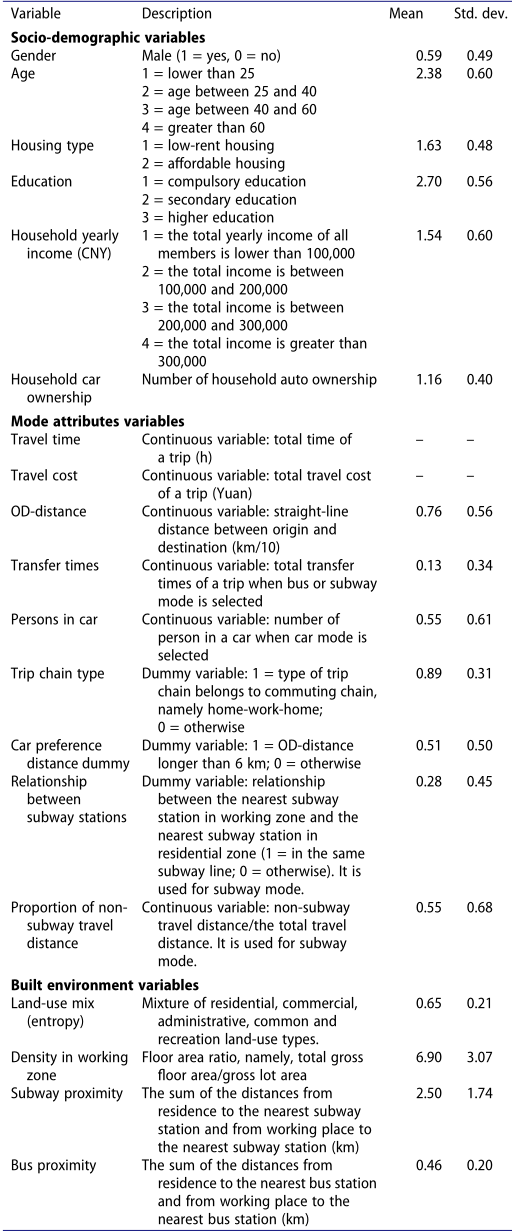

数据结构如下表所示:

表1 变量的统计描述

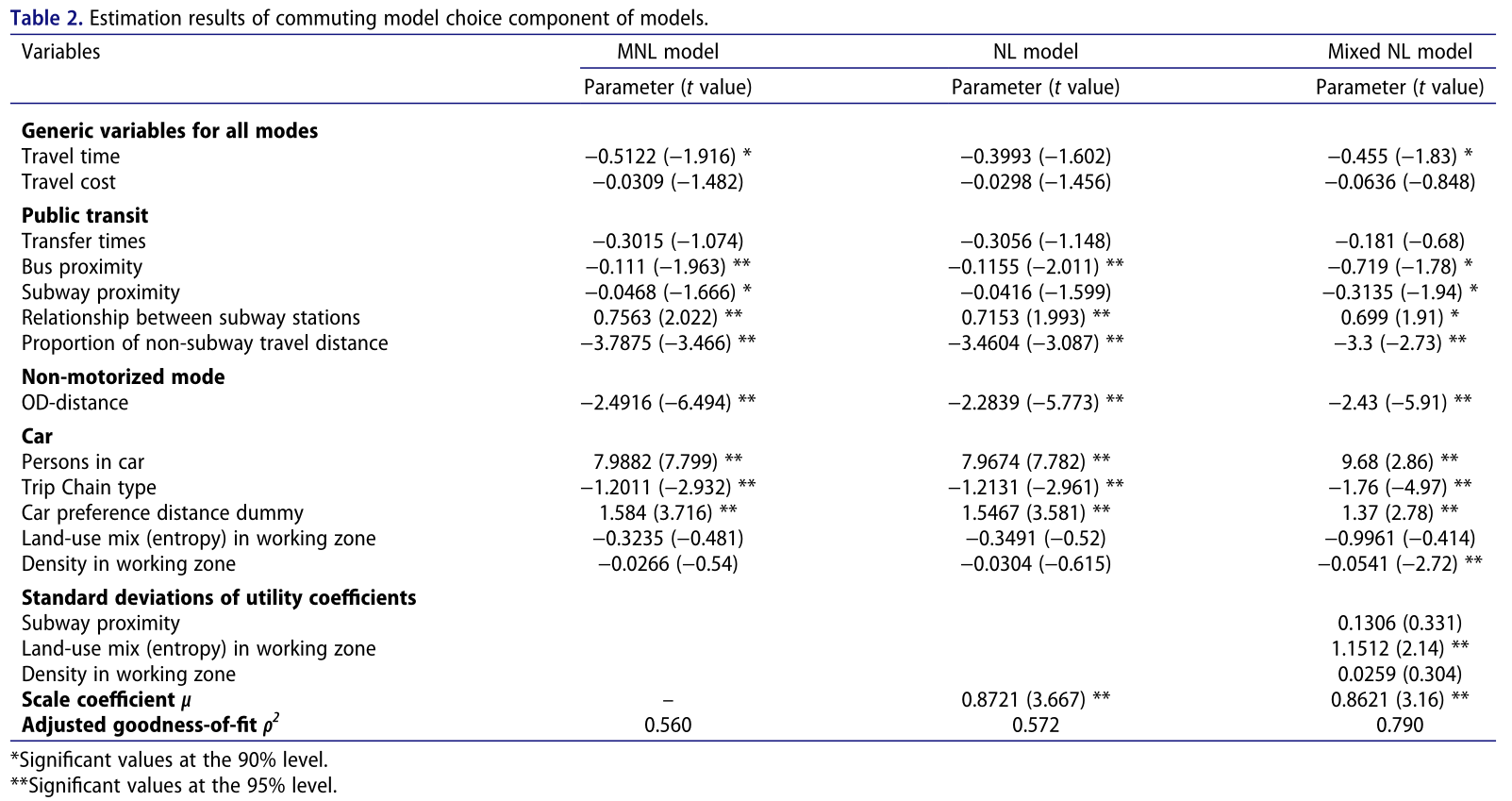

3.4 模型结果

除了本文提出的混合NL模型外,还给出了标准MNL和标准(非随机系数)NL的结果,以供比较。所有系数都假设为对数正态分布。本研究利用Biogeme软件基于极大似然估计法来得到模型参数。剔除与以往研究相比对方式选择没有显著影响或符号不合逻辑的变量后,得到最终规格,如表2所示。

表2 模型通勤模型选择分量的估计结果

可以看出,所有参数的符号都是正确的,大多数参数在95%水平上具有显著性。在NL模型和混合NL模型中,上层尺度参数估计分别为0.8721和0.8621,介于0和1之间,满足嵌套结构的要求。

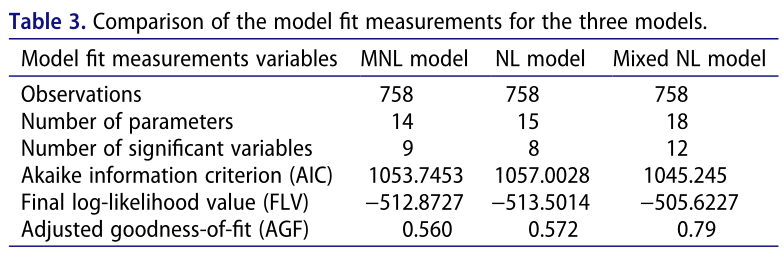

表3 三种模型的模型拟合优度

对方式选择效用函数中的一般变量进行了合理的显著性估计。出行时间和出行成本的相关参数为负。这与以往的研究一致,通勤者更喜欢选择出行时间短、出行成本低的方式。

3.5 直接和交叉弹性分析

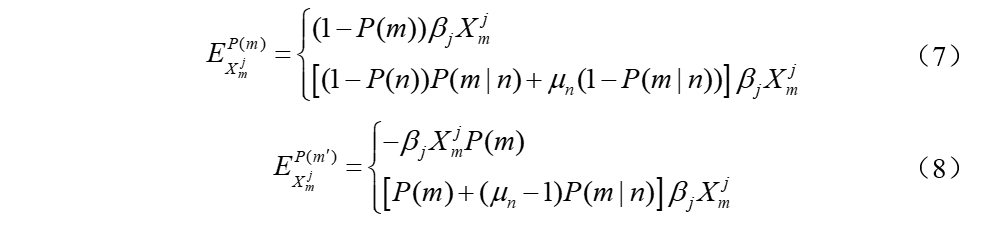

聚合弹性用于显示当自变量发生给定百分比的变化时,选择一种出行方式的概率的变化。其中包括直接弹性和交叉弹性,分别由式(7)和式(8)计算:

式中,和分别为向量和的第个分量。

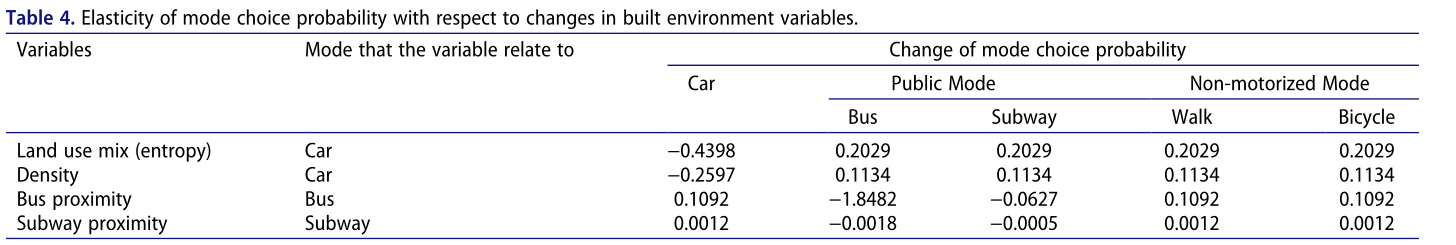

通过使用个体选择,然后通过样本枚举技术进行聚合,建成环境变量的弹性如表4所示。

表4 方式选择概率随建成变量变化的弹性

4 研究结论

本文利用北京市交通委员会最近、全面、权威的调查数据(即第五次住户出行调查),对北京市通勤者的出行方式选择行为进行了识别。在考虑模式属性和建成环境变量的基础上,建立了混合NL模型。通过与赤池信息准则(AIC)、最终对数似然值(FLV)和调整拟合优度(AGF)的比较,证明该模型比MNL和NL模型更适合于该问题。

混合NL模型的估计结果证实了建筑环境在通勤者的模式选择中所起的重要作用,这已经得到了以往研究的广泛认可。当关注公共交通的临近性时,弹性分析结果表明,城市中的公共交通方式,包括公交车和地铁,被通勤者视为一个群体。此外,该模型估计的参数也用于计算主观出行时间价值(VOT)。

本研究虽然描述了一些有趣和重要的结果,但仍具有一定的局限性和未来探索的方向。例如,住宅的自选择是近年来方式选择中的一个有效变量。但是,为了避免住宅自选择的影响,本文仅使用居住在租金较为便宜的住房中的受访者进行建模。这种尝试导致了样本量的显著减少。在未来,可以应用一些复杂的模型结构,克服自选择的影响,然后使用更多的样本数据,使结果更加精确和全面。

5 参考文献

[1] Ashalatha, R., V. S. Manju, and A. B. Zacharia. 2013. “Mode Choice Behaviour of Commuters in Thiruvananthapuram City.” Journal of Transportation Engineering 139 (5): 494–502. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)TE.1943-5436.0000533.

[2] Aziz, H. M. A., N. N. Nagle, A. M. Morton, M. R. Hilliard, D. A. White, and R. N. Stewart. 2018. “Exploring the Impact of Walk-bike Infrastructure, Safety Perception, and Built-environment on Active Transportation Mode Choice: A Random Parameter Model Using New York City Commuter Data.” Transportation 45(5): 1207–1229. 10.1007/s11116-017-9760–8

[3] Bernick, M., and R. Cervero. 1997. In Transit Villages for 21st. Century:

McGraw-Hill. Bierlaire, M. (2003). “BIOGEME: A Free Package for the Estimation of Discrete Choice Models,” Proceedings of the 3rd Swiss Transportation Research Conference, Ascona, Switzerland.Cervero, R. 2007. “Transit-oriented Development’s Ridership Bonus: A Product of Self-selection and Public Policies.” Environment & Planning A 39 (9): 2068–2085. doi:10.1068/a38377.

[4] Chatman, D. G. 2003. “How Intensity and Mixed Uses at the Workplace Affect Personal Commercial Travel and Commute Mode Choice.” Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board 1831 (1):193–201. doi:10.3141/1831-22.

[5] Chen, C., H. Gong, and R. Paaswell. 2008. “Role of the Built Environment on Mode Choice Decisions: Additional Evidence on the Impact of Intensity.” Transportation 35 (3): 285–299. doi:10.1007/s11116-007-9153-5.

[6] Chen, X. M., Q. X. Liu, and G. Du. 2011. “Estimation of Travel Time Values for Urban Public Transport Passengers Based on SP Survey.” Journal of Transportation Systems Engineering and Information Technology 11 (4):77–84. doi:10.1016/S1570-6672(10)60132-8.

[7] Daly, A., S. Zachary, D. Hensher, and Q. Dalvi. 1978. “Improved Multiple Choice Models. Identifying and Measuring the Determinants of Mode Choice.”, 1–16, In Determinants of Travel Demand, edited by D. A. Hensher and M. Q. Dalvi. Sussex: Saxon House

[8] Ding, C., Y. Wang, J. Yang, C. Liu, and Y. Lin. 2016. “Spatial Heterogeneous Impact of Built Environment on Household Auto Ownership Levels: Evidence from Analysis at Traffic Analysis Zone Scales.” Transportation Letters 8 (1): 26–34. doi:10.1179/1942787515Y.0000000004

[9] Ding, C., Y. P. Wang, T. Q. Tang, S. Mishra, and C. Liu. 2018. “Joint Analysis of

the Spatial Impacts of Built Environment on Car Ownership and Travel Mode Choice”. Transportation Research Part D Transport and Environment 60: 28–40. 10.1016/j.trd.2016.08.004

[10] Ding, C., Y. Lin, and C. Liu. 2014. “Exploring the Influence of Built Environment on Tour-based Commuter Mode Choice: A Cross-classified Multilevel Modelling Approach.” Transportation Research Part D Transport & Environment 32: 230–238. doi:10.1016/j.trd.2014.08.001.

[11] Du, Y., S. Jiang, L. Sun, and S. C. Wong. 2011. “Modelling the Mode Choice Behaviour of Visitors to Expo 2010.” Transport 165 (1): 49–62.Ewing, R., and R. Cervero. 2010. “Travel and the Built Environment: A Meta-analysis.” Journal of the American Planning Association 76 (3): 265–294. doi:10.1080/01944361003766766.

[12] Handy, S. L., M. G. Boarnet, R. Ewing, and R. E. Killingsworth. 2002. “How the Built Environment Affects Physical Activity: Views from Urban Planning.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 23 (2): 64–73. doi:10.1016/S0749- 3797(02)00475-0.

[13] Hess, D. 2001. “Effect of Free Parking on Commuter Mode Choice: Evidence from Travel Diary Data.” Transportation Research Record 1753 (1): 35–42. doi:10.3141/1753-05.

[14] Hess, D. B., and P. M. Ong. 2002. “Traditional Neighbourhoods and Automobile Ownership.” Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board 1805 (1): 35–44. doi:10.3141/1805-05.

[15] Hong, J., Q. Shen, and L. Zhang. 2014. “How Do Built Environment Factors Affect Travel Behaviour? A Spatial Analysis at Different Geographic Scales.” Transportation 41 (3): 419–440. doi:10.1007/s11116-013-9462-9.

[16] Kwigizile, V., D. Chimba, and T. Sando. 2011. “A Cross-nested Logit Model for Trip Type-mode Choice: An Application.” Advances in Transportation Studies 23: 29–40.

[17] Levinson, D. M., and Kumar. 1997. “A Intensity and the Journal to Work.” Growth and Change 28 (2): 147–172. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2257.1997.tb00768. x.

[18] Lin, T., D. Wang, and X. Guan. 2017. “The Built Environment, Travel Attitude, and Travel Behaviour: Residential Self-selection or Residential Determination?” Journal of Transport Geography 65: 111–122. doi:10.1016/ j.jtrangeo.2017.10.004.

[19] Mokhtarian, P. L., and X. Cao. 2008. “Examining the Impacts of Residential Self-selection on Travel Behaviour: A Focus on Methodologies.” Transport Reviews 42 (3): 204–228. doi:10.1016/j.trb.2007.07.006.

[20] Wang, D., and T. Lin. 2019. “Built Environment, Travel Behaviour, and Residential Self-selection: A Study Based on Panel Data from Beijing, China.” Transportation 46 (1): 51–74. doi:10.1007/s11116-017-9783-1.

[21] Wang, R. 2011. “Autos, Transit and Bicycles: Comparing the Costs in Large Chinese Cities.” Transport Policy 18 (1): 139–146. doi:10.1016/j. tranpol.2010.07.003.

[22] Wang, X. Q., C. F. Shao, C. Y. Yin, and L. Guan. 2020. “Exploring the Relationships of the Residential and Workplace Built Environment with Commuting Mode Choice: A Hierarchical Cross-classified Structural Equation Model.” Transportation Letters published online, 1–8. doi:10.1080/19427867.2020.1857010

[23] Wang, X. Q., C. F. Shao, C. Y. Yin, and C. J. Dong. 2021. “Exploring the Effects of the Built Environment on Commuting Mode Choice in Neighborhoods near Public Transit Stations: Evidence from China.” Transportation Planning and Technology 44 (1): 111–127. doi:10.1080/03081060.2020.1851453

[24] Wang, Y. 2014. Urban Commuters’ Valuation of Travel Time Reliability Based on Stated Preference Survey. Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing

[25] Wen, C. H., and F. S. Koppelman. 2001. “The Generalized Nested Logit Model.”Transportation Research Part B 35 (7): 627–641. doi:10.1016/S0191-2615(00) 00045-X.

[26] Yin, C. Y., C. F. Shao, and X. Q. Wang. 2020. “Exploring the Impact of Built Environment on Car Use: Does Living near Urban Rail Transit Matter?” Transportation Letters 12 (6): 391–398. doi:10.1080/19427867.2019.1611196.

[27] Zegras, C. 2010. “The Built Environment and Motor Vehicle Ownership and Use: Evidence from Santiago De Chile.” Urban Studies 47 (8): 1793–1817. doi:10.1177/0042098009356125.