采用随机森林方法模拟家庭搬迁行为

论文题目:采用随机森林方法模拟家庭搬迁行为 (Adopting a random forest approach to model household residential relocation behavior)

论文作者:Fei Xue , Enjian Yao

论文期刊:Cities

论文网址:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264275122000646?via=ihub

摘要:

虽然有很多研究考察了居民搬迁对出行行为的影响,但很少有研究影响因素对居民搬迁行为的影响。本研究利用北京903个搬迁家庭的数据,建立随机森林模型,评估建筑环境、通勤距离、房价、居住面积、家庭社会经济和人口属性对有通勤工人或学生的家庭居住搬迁行为的相对重要性和影响方式。结果表明,建筑环境对搬迁行为的影响最大,其次是房价、通勤距离、社会经济和人口属性以及居住面积。此外,研究发现建筑环境、通勤距离和房价对居民搬迁行为的影响呈非线性且存在阈值。本研究可帮助城市规划者和管理者定量了解影响因素对居民搬迁行为的影响,为规划者和房地产开发公司规划开发相关土地提供参考价值。

关键词:出行行为,机器学习,土地利用,建成环境,非线性关联,阈值影响(Travel behavior, Machine learning, Land use, Built environment, Nonlinear associations, Threshold effects)

1 研究背景

随着经济的快速发展,人口过剩、交通拥堵、住房短缺、空气污染等问题逐渐在世界各大城市出现。为了缓解这些问题,基于交通导向发展(TOD)概念的新区或新城的设计和建设被认为是一个主要的解决方案,并被许多国家采用,如美国、英国、日本、新加坡、中国、韩国、伊朗等。现有的关于居住行为的研究可以分为居住地点选择和居住迁移行为。近年来,大量的研究对世界各地的家庭住宅区位选择进行了研究。开发新区或新城的目的是为了吸引足够的人从拥挤的大城市搬到新区,从而缓解大城市的人口压力。结果表明,建筑环境、工作通勤距离、上学通勤距离、住房价格和家庭社会经济属性都对住宅搬迁行为有影响。对于有通勤员工而无学生的家庭,或有学生而无通勤员工的家庭,上述因素是否影响其住宅搬迁行为,以及其他因素,如孩子的出生和居住区域,是否对住宅搬迁行为有影响是值得探讨的。此外,在知道哪些因素影响住宅搬迁行为后,这些因素是如何影响的,是否具有非线性关系和阈值效应,这些因素的影响等级仍然需要进一步探讨。这些研究成果可以帮助城市规划者制定相应的城市规划。本研究旨在利用机器学习方法——随机森林法来填补上述研究空白,同时以北京为例,探讨建筑环境、通勤距离、住房价格、居住面积、家庭社会经济和人口属性对通勤工人或学生家庭住宅搬迁行为的相对重要性,并探讨这些影响因素如何影响搬迁行为。本研究有望丰富家庭居住行为的研究,并有望帮助城市规划者和管理者了解住宅与交通和土地利用的互动关系。本研究还将为制定新区和新城规划提供理论支持和规划指标的参考范围。

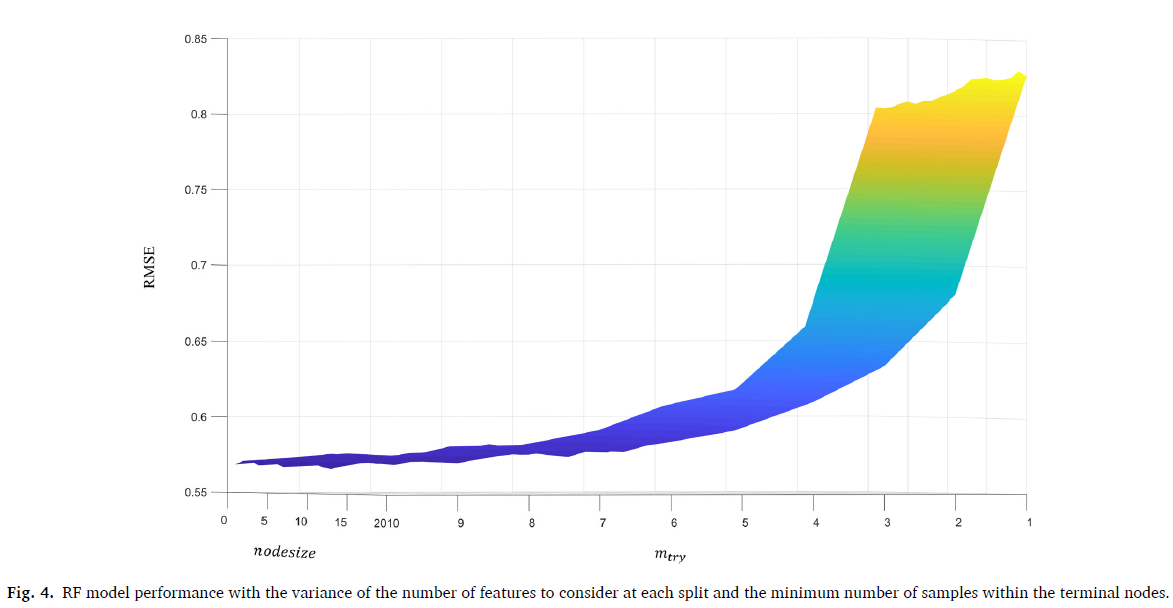

2变量和数据

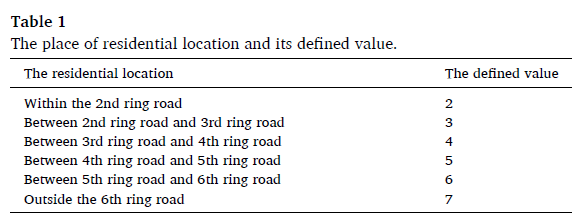

本研究采用搬迁方向作为连续值来表示家庭居住搬迁行为。为了方便相关部门制定规划和管理政策,本研究采用环路来定位住宅,而不是大范围的界定郊区和城区。具体为住宅所在区域及其定义值如表1所示。因此,搬迁方向是用搬迁后居住地所在的环路位置减去之前居住地所在的环路位置来计算。本研究选取建筑环境特征变化、住房价格变化、居民搬迁前后平均通勤距离变化、家庭社会经济和人口属性、住宅居住面积作为自变量,探讨其对家庭居住搬迁的影响。为了对应因变量,本研究用当前住宅各建成环境特征的值减去前一住宅相应的值来表示建成环境特征的变化,用当前住宅单位房价减去前一住宅相应的单位房价来表示房价变化,并用当前居住地家庭中工人和学生的平均通勤距离减去对应的前居住地的平均通勤距离来表示通勤距离的变化。

表 1 住宅位置及其定义值对照表

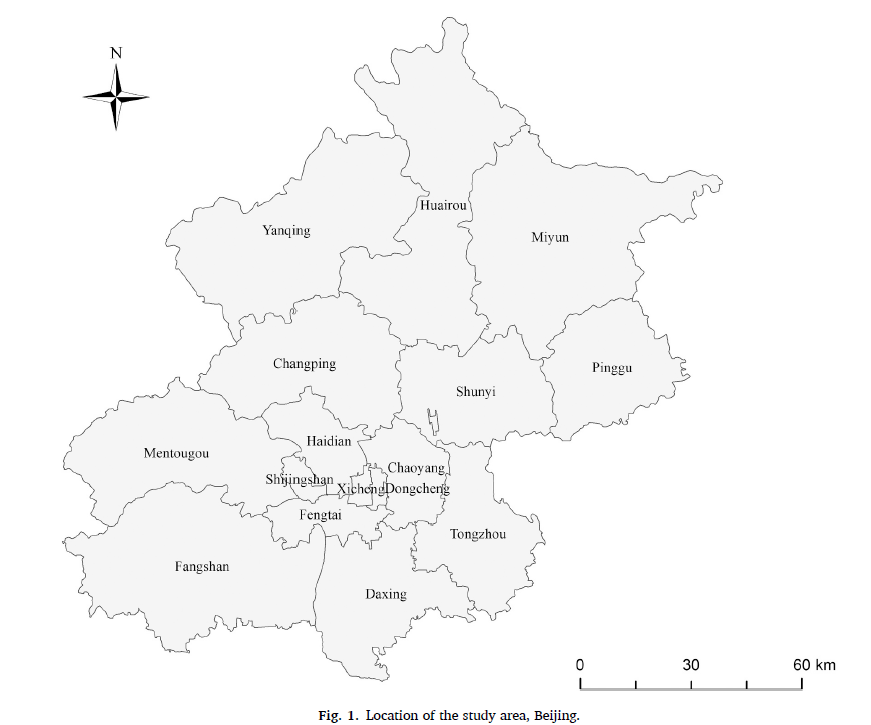

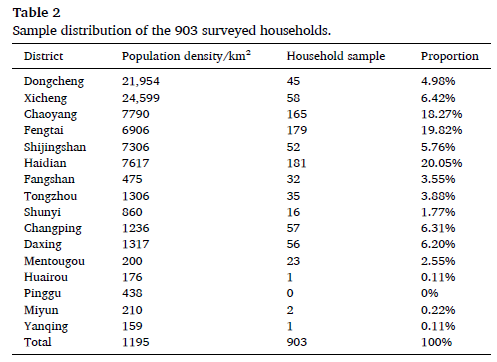

本研究使用的数据来自北京市交通委员会于2014年9月至11月组织的第五次北京居民出行调查。本次调查以北京市全市为调查区域,随机调查了全市40003户家庭。全市被调查家庭抽样率为0.60%。调查记录了家庭的社会经济和人口属性、每个家庭成员的通勤信息以及家庭住宅的变化。研究区域如图1所示,903个被调查家庭的分布情况见表2。

图 1 研究范围示意图

表 2 调查对象样本分布表

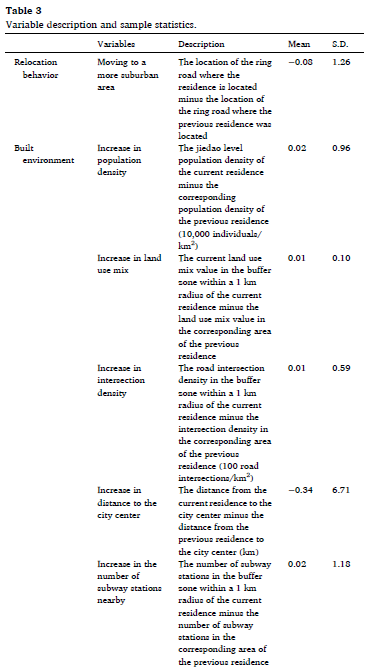

调查数据统计如表3所示。可以发现,四分之一的家庭在新住宅的环路位置比他们的原有住宅小。在北京,四环以内的区域一般被认为是城区,四环以外的区域被认为是郊区。环路数字越大表示离市中心越远。因此,在数据集中,迁往市区的家庭比迁往郊区的家庭更多。

表 3 变量描述和样本统计表

4方法

随机森林(RF)是由Breiman提出的一种袋式集合学习方法。该方法通过训练数据的自举样本建立多个决策树,并将它们结合起来以获得准确和稳定的预测。它已被证明在采用少量计算资源的情况下表现非常好。具体来说,变量重要性可以衡量每个自变量对因变量的影响。而部分依赖图可以在考虑到模型中所有其他自变量的平均影响后,呈现出自变量对因变量的边际影响的图形描述。RF不同于传统的回归方法,它是基于预先确定的关系的假设(如线性、对数线性和n次方),因此可以反映自变量和因变量之间的真实关系。因此,本研究选择了RF方法,该方法的工作过程如图2所示。

图 2 随即森林方法说明图

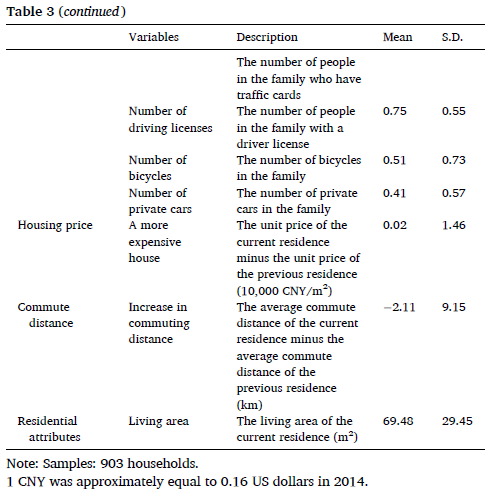

为了探究建成环境、通勤距离、房价、居住面积、家庭社会经济和人口属性对居民搬迁行为的影响,本研究首先利用R软件构建了十九输入一输出RF基本模型。Breiman提出分裂变量的数量应为p/3,即7 (p = 19是模型中所有自变量的总数)。因此,这个基本模型选择ntree = 500, mtry = 7,并且对节点大小nodesize没有任何限制。然后,对该模型的ntree参数进行优化。其中,建立树数为10 ~ 500棵,增量为10的RF基本模型,选取均方误差(mean square error, MSE)指标作为判断标准。模型的性能如图3所示。

图 3 RF模型的基本性能与树的数量关系图

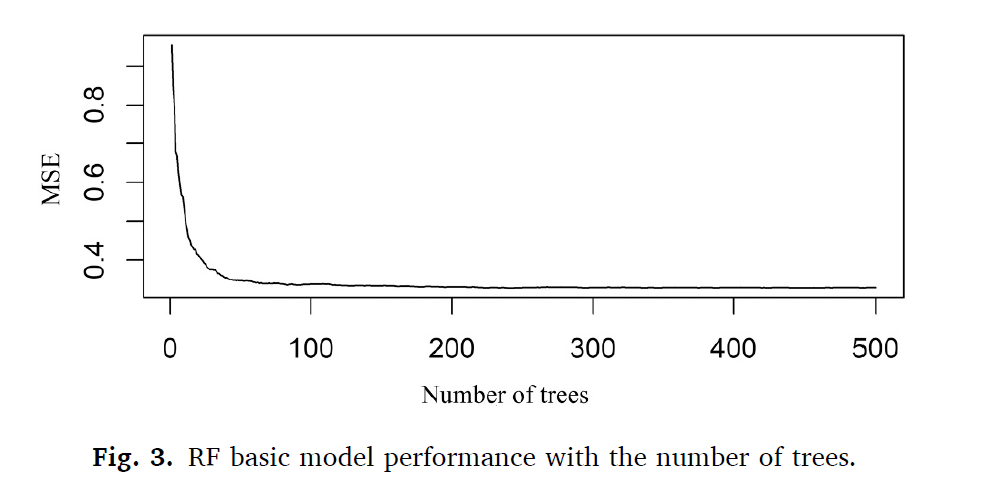

可以发现,当树超过200株时,随着树的增加,MSE的下降不显著。因此,本研究采用200棵树的森林规模。然后,选取均方根误差(RMSE)作为判断标准,采用全笛卡尔网格搜索法(full Cartesian grid search)对 (从1到10,增量为1)和nodesize (从1到20,增量为1)的每个组合进行评估,如图4所示。

图 4 RF模型的性能与每次分裂时要考虑的特征数量的方差和终端节点内的最小样本数量关系图

5结果

5.1. 相对重要性分析

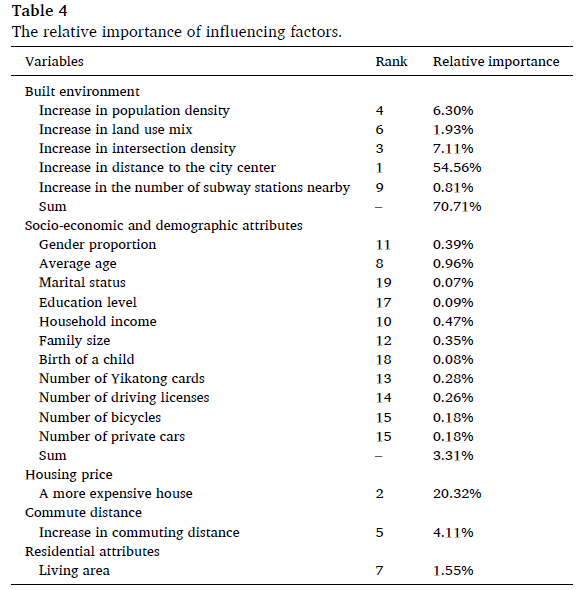

影响因素对居民搬迁行为的相对重要性估计结果见表4。可以发现,建筑环境特征对搬迁行为的影响最大,占70.71%;其次是住房价格,占20.32%;再次是通勤距离和家庭社会经济及人口属性,分别占4.11%和3.31%;居住面积的影响最小,占1.55%。结果显示,住宅的建筑环境是影响家庭住宅搬迁行为的最重要因素。居住地附近的建筑环境特征可以表征城市化程度、交通便利性、街道设计和住宅区的土地使用情况。为了获得良好的生活体验,在搬迁住宅时,人们首先考虑住宅周围的建筑环境。这与之前的研究结果一致,即建筑环境特征会显著影响人们对居住地的选择(Kroesen,2019;Wolday等人,2018)。

表 4 影响因素的相对重要性表

5.2. 非线性效应分析

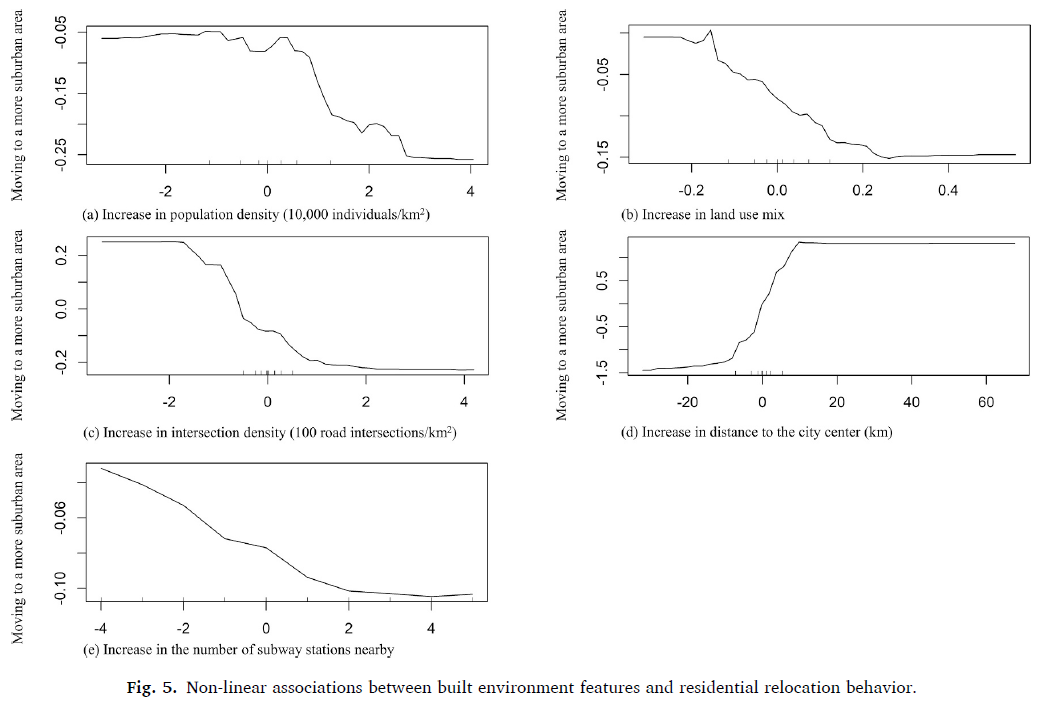

建筑环境、住房价格和通勤距离对搬迁行为的关系如图5和6所示。纵轴代表搬迁方向的数值,横轴代表各影响因素的数值。图5展示了在考虑了其他自变量的平均影响后,建筑环境特征,即人口密度、土地利用组合、道路交叉口密度、到市中心的距离和附近地铁站的数量,分别对住宅搬迁行为的影响。可以发现,人口密度的增加、土地利用组合的增加、道路交叉口密度的增加、附近地铁站数量的增加与迁往更郊外的地区呈负相关,而与市中心距离的增加呈正相关。这些结果验证了这样一个事实:城市地区的人口密度、土地利用组合、道路交叉口密度和地铁站数量都大于郊区,城市地区比郊区更接近市中心。

图 5 建筑环境特征与居民搬迁行为的非线性关系图

图6展示了在其他影响因素控制下,住房价格和通勤距离分别对住宅搬迁行为的影响。结果显示,更高住房价格与搬迁到郊区是负相关的,而更长的通勤距离是正相关的。结果验证了,中国郊区房价普遍比市区便宜,而搬到郊区后,通勤距离会变长。

图 6 房价和居民搬迁行为、通勤距离和居民搬迁行为之间的非线性关系图

6结论

本研究得到了以下结论:首先,城市规划部门在制定新区、新城规划和人口再分配规划时,可以通过居住用地规划来控制人口规模。其次,在新区、新城居住用地规划过程中,规划者应更加关注规划居住区周边的建筑环境特征、房价以及居住人群的通勤距离。第三,在规划居住区附近的建筑环境特征时,应首先考虑住宅用地与城市中心的距离。此外,建筑环境特征、房价和通勤距离对居民居住迁移行为具有非线性和门槛效应。在制定相关规划时,需要以具体的居住区为参考,设定相关的规划指标值。本研究结果可帮助城市规划者和管理者更好地了解建筑环境、房价、通勤距离、居住面积以及家庭社会经济和人口属性对居民搬迁行为的影响。并可为城市规划部门和房地产开发公司提供准确的指标值,供其制定住宅规划时参考。

本研究也存在一定的局限性,可以在今后的研究中进一步完善。首先,本研究仅以中国一个城市的数据为例,尽管所提出的方法可以很容易地应用于其他城市。此外,本研究没有考虑居民的旅行和生活态度和喜好,这些都不包括在调查中。在未来的研究中,学者们可以采用这种方法使用其他城市或国家的数据进行研究。同时,他们可以将人们的出行和生活态度和偏好加入到模型中,探索他们在居民搬迁行为中的作用。

参考文献

[1] Adhikari, B., Hong, A., & Frank, L. D. (2020). Residential relocation, preferences, life events, and travel behavior: A pre-post study. Research in Transportation Business and Management, 36.

[2] Aditjandra, P. T., Mulley, C., & Cao, X. J. (2016). Exploring changes in public transport use and walking following residential relocation: A British case study. Journal of Transport and Land Use, 9, 77–95.

[3] Ardeshiri, A., & Vij, A. (2019). Lifestyles, residential location, and transport mode use: A hierarchical latent class choice model. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 126, 342–359.

[4] Beenackers, M. A., Foster, S., Kamphuis, C. B. M., Titze, S., Divitini, M., Knuiman, M., Van Lenthe, F. J., & Giles-Corti, B. (2012). Taking up cycling after residential relocation: Built environment factors. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 42, 610–615.

[5] Bhat, C. R., & Guo, J. Y. (2007). A comprehensive analysis of built environment characteristics on household residential choice and auto ownership levels. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological, 41, 506–526.

[6] Cao, J., & Ermagun, A. (2017). Influences of LRT on travel behaviour: A retrospective study on movers in Minneapolis. Urban Studies, 54, 2504–2520.

[7] Chen, E., & Ye, Z. (2021). Identifying the nonlinear relationship between free-floating bike sharing usage and built environment. Journal of Cleaner Production, 280, Article 124281.

[8] Cheng, L., Chen, X., De Vos, J., Lai, X., & Witlox, F. (2019). Applying a random forest method approach to model travel mode choice behavior. Travel Behaviour and Society, 14, 1–10.

[9] Cheng, L., De Vos, J., Zhao, P., Yang, M., & Witlox, F. (2020). Examining non-linear built environment effects on elderly’s walking: A random forest approach. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 88, Article 102552.

[10] de Groot, C., Mulder, C. H., & Manting, D. (2011). Intentions to move and actual moving behaviour in the Netherlands. Housing Studies, 26, 307–328.

[11] De Vos, J., Cheng, L., & Witlox, F. (2020). Do changes in the residential location lead to changes in travel attitudes? A structural equation modeling approach: Transportation.

[12] De Vos, J., Derudder, B., Van Acker, V., & Witlox, F. (2012). Reducing car use: Changing attitudes or relocating? The influence of residential dissonance on travel behavior. Journal of Transport Geography, 22, 1–9.

[13] De Vos, J., Ettema, D., & Witlox, F. (2018). Changing travel behaviour and attitudes following a residential relocation. Journal of Transport Geography, 73, 131–147.

[14] De Vos, J., Ettema, D., & Witlox, F. (2019). Effects of changing travel patterns on travel satisfaction: A focus on recently relocated residents. Travel Behaviour and Society, 16, 42–49.

[15] De Vos, J., & Witlox, F. (2016). Do people live in urban neighbourhoods because they do not like to travel? Analysing an alternative residential self-selection hypothesis. Travel Behaviour and Society, 4, 29–39.

[16] Desai, S., & Ouarda, T. B. M. J. (2021). Regional hydrological frequency analysis at ungauged sites with random forest regression. Journal of Hydrology, 594, Article 125861.

[17] Ding, C. (2004). Urban spatial development in the land policy reform era: Evidence from Beijing. Urban Studies, 41, 1889–1907.

[18] Ding, C., Cao, X.(. J.)., & Næss, P. (2018). Applying gradient boosting decision trees to examine non-linear effects of the built environment on driving distance in Oslo. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 110, 107–117.

[19] Ettema, D., & Nieuwenhuis, R. (2017). Residential self-selection and travel behaviour: What are the effects of attitudes, reasons for location choice and the built environment? Journal of Transport Geography, 59, 146–155.

[20] Ewing, R., & Cervero, R. (2010). Travel and the built environment. Journal of the American Planning Association, 76, 265–294.

[21] Fatmi, M. R., Chowdhury, S., & Habib, M. A. (2017). Life history-oriented residential location choice model: A stress-based two-tier panel modeling approach. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 104, 293–307.

[22] Fatmi, M. R., & Habib, M. A. (2017). Modelling mode switch associated with the change of residential location. Travel Behaviour and Society, 9, 21–28.

[23] Giles-Corti, B., Bull, F., Knuiman, M., McCormack, G., Van Niel, K., Timperio, A., Christian, H., Foster, S., Divitini, M., Middleton, N., & Boruff, B. (2013). The relocation: Longitudinal results from the RESIDE study. Social Science and Medicine, 77, 20–30.

[24] Guan, X., & Wang, D. (2019). Residential self-selection in the built environment-travel behavior connection: Whose self-selection? Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 67, 16–32.

[25] Guidon, S., Wicki, M., Bernauer, T., & Axhausen, K. (2019). The social aspect of residential location choice: On the trade-off between proximity to social contacts and commuting. Journal of Transport Geography, 74, 333–340.

[26] Harrison, J. W., Lucius, M. A., Farrell, J. L., Eichler, L. W., & Relyea, R. A. (2021). Prediction of stream nitrogen and phosphorus concentrations from high-frequency sensors using random forests regression. Science of the Total Environment, 763, Article 143005.

[27] Heaton, T., Fredrickson, C., Fuguitt, G. V., & Zuiches, J. J. (1979). Residential preferences, community satisfaction, and the intention to move. Demography, 16, 565–573.

[28] Ibrahim, M. R. (2017). How do people select their residential locations in Egypt? The case of Alexandria. Cities, 62, 96–106.

[29] Klinger, T., & Lanzendorf, M. (2016). Moving between mobility cultures: What affects the travel behavior of new residents? Transportation, 43, 243–271.

[30] Krizek, K. J. (2003). Residential relocation and changes in urban travel: Does neighborhood-scale urban form matter? Journal of the American Planning Association, 69, 265–281.

[31] Kroesen, M. (2019). Residential self-selection and the reverse causation hypothesis: Assessing the endogeneity of stated reasons for residential choice. Travel Behaviour and Society, 16, 108–117.

[32] Lau, J. C. Y., & Chiu, C. C. H. (2013). Dual-track urbanization and co-location travel behavior of migrant workers in new towns in Guangzhou, China. Cities, 30, 89–97.

[33] Lee, K. O. (2014). Why do renters stay in or leave certain neighborhoods? The role of neighborhood characteristics, housing tenure transitions, and race. Journal of Regional Science, 54, 755–787.

[34] Lin, T., Wang, D., & Zhou, M. (2018). Residential relocation and changes in travel behavior: What is the role of social context change? Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 111, 360–374.

[35] Liu, J., Wang, B., & Xiao, L. (2021). Non-linear associations between built environment and active travel for working and shopping: An extreme gradient boosting approach. Journal of Transport Geography, 92, Article 103034.

[36] Morgan, N. (2020). The stickiness of cycling: Residential relocation and changes in utility cycling in Johannesburg. Journal of Transport Geography, 85, Article 102734.

[37] Ramezani, S., Hasanzadeh, K., Rinne, T., Kajosaari, A., & Kytt¨a, M. (2021). Residential relocation and travel behavior change: Investigating the effects of changes in the built environment, activity space dispersion, car and bike ownership, and travel attitudes. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 147, 28–48.

[38] Scheiner, J., & Holz-Rau, C. (2013). Changes in travel mode use after residential relocation: A contribution to mobility biographies. Transportation, 40, 431–458.

[39] Schwanen, T., & Mokhtarian, P. L. (2004). The extent and determinants of dissonance between actual and preferred residential neighborhood type. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 31, 759–784.

[40] Shao, Q., Zhang, W., Cao, X., Yang, J., & Yin, J. (2020). Threshold and moderating effects of land use on metro ridership in Shenzhen: Implications for TOD planning. Journal of Transport Geography, 89, Article 102878.

[41] Shaykh-Baygloo, R. (2020). A multifaceted study of place attachment and its influences on civic involvement and place loyalty in Baharestan new town. Iran. Cities, 96, Article 102473.

[42] Sun, L., Zhang, T., Liu, S., Wang, K., Rogers, T., & Yao, L. (2021). Reducing energy consumption and pollution in the urban transportation sector: A review of policies and regulations in Beijing. Journal of Cleaner Production, 285, Article 125339.

[43] Tao, T., Wu, X., Cao, J., Fan, Y., Das, K., & Ramaswami, A. (2020). Exploring the nonlinear relationship between the built environment and active travel in the twin cities. Journal of Planning Education and Research..

[44] Tu, M., Li, W., Orfila, O., Li, Y., & Gruyer, D. (2021). Exploring nonlinear effects of the built environment on ridesplitting: Evidence from Chengdu. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 93.

[45] Turban, D. B., Campion, J. E., & Eyring, A. R. (1992). Factors relating to relocation decisions of research and development employees. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 41, 183–199.

[46] Van Acker, V., Mokhtarian, P. L., & Witlox, F. (2014). Car availability explained by the structural relationships between lifestyles, residential location, and underlying residential and travel attitudes. Transport Policy, 35, 88–99.

[47] van Ham, M., & Clark, W. A. V. (2009). Neighbourhood mobility in context: Household moves and changing neighbourhoods in the Netherlands. Environment and Planning A, 41, 1442–1459.

[48] Vongpraseuth, T., Seong, E. Y., Shin, S., Kim, S. H., & Choi, C. G. (2020). Hope and reality of new towns under greenbelt regulation: The case of self-containment or transit-oriented metropolises of the first-generation new towns in the Seoul metropolitan area. South Korea. Cities, 102, Article 102699.

[49] Wang, D., He, S., Webster, C., & Zhang, X. (2019). Unravelling residential satisfaction and relocation intention in three urban neighborhood types in Guangzhou, China. Habitat International, 85, 53–62.

[50] Wang, D., & Lin, T. (2019). Built environment, travel behavior, and residential self-selection: A study based on panel data from Beijing, China. Transportation, 46, 51–74.

[51] Wang, F., Mao, Z., & Wang, D. (2020). Residential relocation and travel satisfaction change: An empirical study in Beijing, China. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 135, 341–353.

[52] Wolday, F., Cao, J., & Næss, P. (2018). Examining factors that keep residents with high transit preference away from transit-rich zones and associated behavior outcomes. Journal of Transport Geography, 66, 224–234.

[53] Wolday, F., Næss, P., & Cao, X.(. J.). (2019). Travel-based residential self-selection: A qualitatively improved understanding from Norway. Cities, 87, 87–102.

[54] Woods, L., & Ferguson, N. (2014). The influence of urban form on car travel following residential relocation: A current and retrospective study in Scottish urban areas. Journal of Transport and Land Use, 7, 95–104.

[55] Wu, S.s., Zhuang, Y., Chen, J., Wang, W., Bai, Y., & Lo, S.m. (2019). Rethinking bus-to-metro accessibility in new town development: Case studies in Shanghai. Cities, 94, 211–224.

[56] Wu, X., Tao, T., Cao, J., Fan, Y., & Ramaswami, A. (2019). Examining threshold effects of built environment elements on travel-related carbon-dioxide emissions. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 75, 1–12.

[57] Xu, F., Ho, H. C., Chi, G., & Wang, Z. (2019). Abandoned rural residential land: Using machine learning techniques to identify rural residential land vulnerable to be abandoned in mountainous areas. Habitat International, 84, 43–56.

[58] Xu, Y., Yan, X., Liu, X., & Zhao, X. (2021). Identifying key factors associated with ridesplitting adoption rate and modeling their nonlinear relationships. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 144, 170–188.

[59] Xue, C. Q. L., Wang, Y., & Tsai, L. (2013). Building new towns in China - a case study of Zhengdong New District. Cities, 30, 223–232.

[60] Xue, F., Yao, E., & Jin, F. (2020). Exploring residential relocation behavior for families with workers and students; a study from Beijing. China. Journal of Transport Geography, 89, Article 102893.

[61] Yang, M., Wu, J., Rasouli, S., Cirillo, C., & Li, D. (2017). Exploring the impact of residential relocation on modal shift in commute trips: Evidence from a quasi-longitudinal analysis. Transport Policy, 59, 142–152.

[62] Yin, G., Liu, Y., & Wang, F. (2018). Emerging Chinese new towns: Local government-directed capital switching in inland China. Cities, 79, 102–112.

[63] Yu, B., Zhang, J., & Li, X. (2017). Dynamic life course analysis on residential location choice. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 104, 281–292.

[64] Zamani, B., & Arefi, M. (2013). Iranian new towns and their Urban Management issues: A critical review of influential actors and factors. Cities, 30, 105–112.

[65] Zarabi, Z., Manaugh, K., & Lord, S. (2019). The impacts of residential relocation on commute habits: A qualitative perspective on households’ mobility behaviors and strategies. Travel Behaviour and Society, 16, 131–142.

[66] Zhang, Y., Yao, E., Zhang, R., & Xu, H. (2019). Analysis of elderly people’s travel behaviours during the morning peak hours in the context of the free bus programme in Beijing, China. Journal of Transport Geography, 76, 191–199.

[67] Zhao, P., & Zhang, Y. (2018). Travel behaviour and life course: Examining changes in car use after residential relocation in Beijing. Journal of Transport Geography, 73, 41–53.